“I had the full-blown mystical revelatory experience – the big psychedelic multi-coloured light and sound show.”

This is how Steve recalls his first dose of a hallucinogenic drug, psilocybin, the psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms.

His experience was part of a clinical trial that some scientists are calling a major step towards a revolution in the treatment of depression. It is a trial complicated by the fact that the drug it is testing is illegal. Psilocybin is a Schedule 1 controlled substance; its use is very strictly regulated.

Part of the definition of a Schedule 1 drug is that it is not used medicinally. But this trial, which scanned of the brains of participants after their treatment with psychedelics, painted an extraordinary physical picture of the effect and the experience. The brain scans showed “more connectivity” between different brain regions.

The researchers say their findings show how hallucinogenics break a depressed person “out of a rut of negative thinking” – that psilocybin “reintegrates” a depressed brain, making it more fluid, flexible and connected.

So how does it feel to have your brain reintegrated by psychedelic drugs?

“It’s an ineffable experience – words like the ones we’re using now are just not enough,” Steve told BBC Radio 4’s Inside Science.

“With the first dose, I felt joy like I’ve never experienced – and more like myself than I’ve ever felt.”

But the second dose in the trial, he said, was very dark.

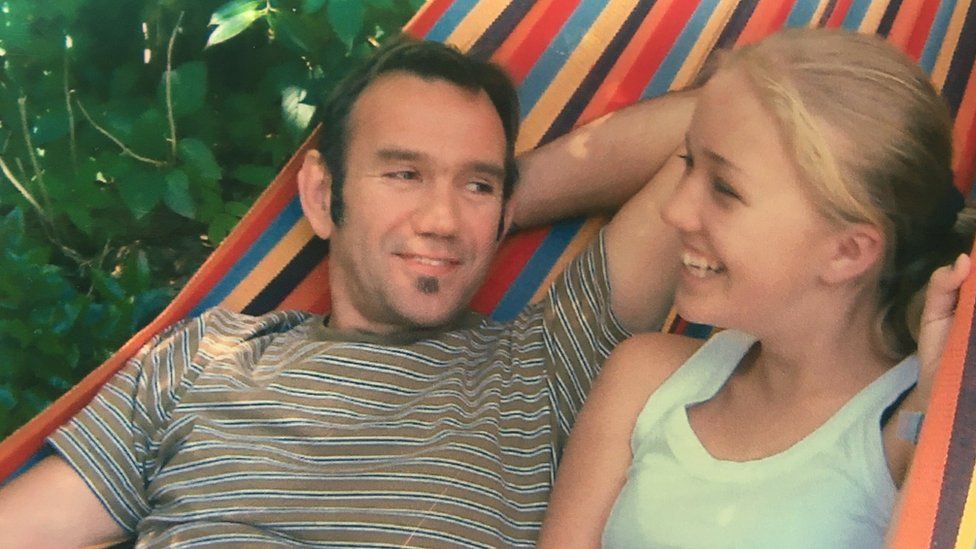

Steve, who is now in his 60s, was diagnosed with depression more than 30 years ago.

Traditional antidepressants simply did not work for him.

Those existing drugs work by increasing the levels of a chemical called serotonin in the brain. That is one of the chemical messengers that relays signals from one part of the brain to another; low serotonin has been associated with depression since the 1960s.

But while antidepressant drugs that “correct” that serotonin imbalance numbed the lows for Steve – lows that he said could often make him feel that his life was completely worthless – they also numbed the highs.

“[When I was taking those drugs] there was just no colour – no joy in my life.

“You end up living like a functional zombie.”

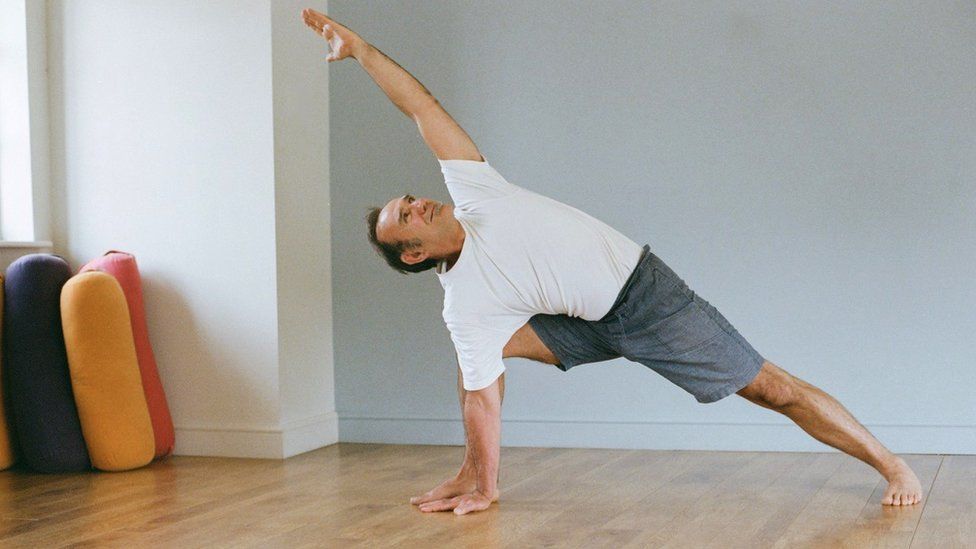

Steve made the difficult decision to come off the drugs. He continued his long-term regime of meditation, yoga and running that he says has helped him to manage his depression all these years.

But when he heard an interview on the radio about a new trial investigating the use of psychedelics for depression, he called to volunteer.

“I had to wait a year, and selection criteria were very tough.”

Participants had to show, not only that other antidepressants had not been successful in treating their depression, but that they did not have other conditions, including psychosis, that could make the use of psychedelics particularly risky.

Finally, after careful vetting, and under the supervision of a professional therapist, Steve was given his first dose of psilocybin.

“It felt wonderful,” he recalled. “I felt more connected to myself – it was extraordinary.

“It took from not knowing myself at all to having a sense of what my place was in the greater scheme of things.”

What Steve felt has shown up in brain scans.

Images of participants’ brains before and after a dose of “magic mushroom juice” showed what lead researcher Prof David Nutt, from the Imperial Centre for Psychedelic Research, described as a brain reset.

The images showed that psychedelics induced a connectivity, where different brain regions communicated with each other much more, revealing new ways of thinking.

“I had no conscious sense of my brain being ‘scrambled’ but certainly there was a lot more going on there than I could ever have imagined,” said Steve.

His second experience with psilocybin though, was much more difficult.

“I had to wrestle with those feelings and emotions that I tend to suppress.

“So, the second session, although it was hard work, was probably therapeutically more useful, because I had to deal with the stuff that I just hadn’t dealt with before.

Prof Nutt is campaigning for these illegal drugs to be reclassified for research purposes, in order to make trials like his less legally complicated – and to enable what he says could be a revolution in the treatment of depression.

But the drug, both Steve and Prof Nutt stressed, is no magic antidepressant bullet.

In the trial, the treatment was combined with professional therapy. Ongoing work at the Centre for Psychedelic Research, and elsewhere, is focused on developing and safely testing new therapeutic protocols, ways to combine drug treatment with therapy in order to treat depression in a new way.

“The drug gives us part of a healing process. It exposes you to different possibilities – another way of being,” said Steve.

The real work, he says, starts after the experience and needs the guidance of a therapist to make it meaningful.

“It’s one thing developing a drug, but we need protocols to help people like me,” said Steve.

“But I would not change the experience for anything – it was wonderful – and I don’t expect ever to experience anything like it again.”